The Cotsen Textile Traces Study Center is home to thousands of remarkable textile fragments. However, the history of these textiles can sometimes be as fragmented as they are. Yet, we can often find clues to their origins by looking at the unique details of each fragment. In an analysis of one such textile from the Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection, a batik textile from the Javanese north coast, we will see how color, pattern, and other key features of a textile can be used to unlock a piece of its past. This textile, referred to here as T-1223, is only a fragment of a larger textile, and very little is known about its history. However, the Cotsen Collection’s textile fragment can be attributed to a specific location and style by analyzing both motif and geometric patterns.

Batik is an Indonesian term for the wax-resist dyeing process or a fabric patterned with this process. [i] This style derived from an island-wide desire for ornate objects and sacred garments. [ii] In Javanese batik textiles, certain colors, patterns, and motifs are common. The characteristic geometric patterns of batik textiles include nature-related patterns and angled geometrical symbols. The batik-making technique also requires the use of wax-resistant dyes such as indigo (indigofera), soft brown (soga), and deep auburn (morinda citrifolia).

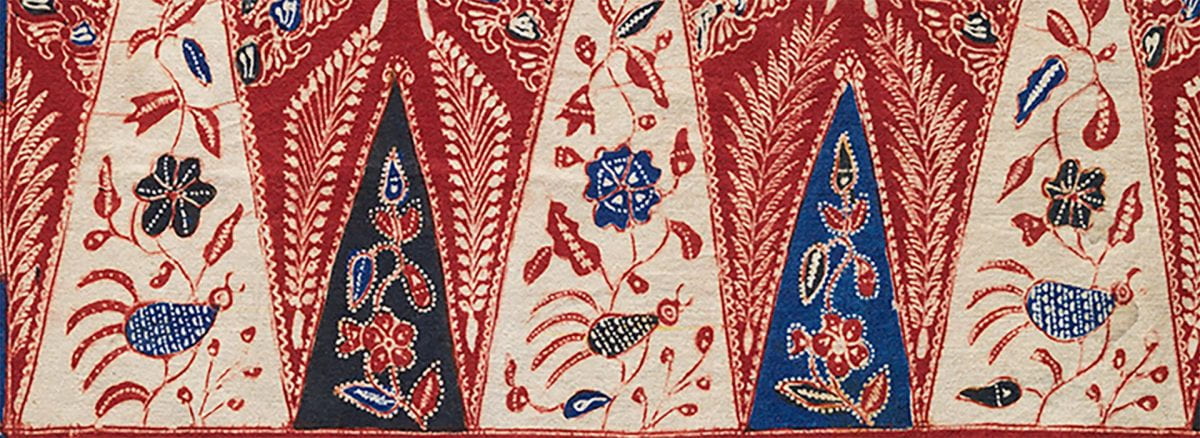

Batiks from Java’s north coast became especially popular through flourishing coastal trade markets starting as early as the fifteenth century. [iii] Because of its advantageous position on the north coast, the island was well-connected with its neighbors such as India, China, mainland Indonesia, and even some European countries. [iv] This allowed for an exchange of goods as well as culture and art between the countries. As a result, the region’s trading partners heavily influenced the common features of Javanese batik textiles. [v] One example of this can be found on a textile from the Victoria and Albert Museum’s (V&A) collection originating from the northwest coast of Java, specifically the Cirebon-Indramayu region (see above). Batiks from this region are known for their blend of rich geometric detail with Chinese-influenced natural motifs and color. As exemplified with the V&A’s skirt cloth, textiles from this region share striking similarities with the Cotsen fragment, T-1223. Comparing T-1223 to the V&A’s textile can help identify where the T-1223 may have been created and its original style.

Like the Cotsen Collection’s batik fragment, T-1223, the Victoria and Albert collection’s skirt cloth showcases flowering, natural motifs around borders and in nearly every blank space. Among the depictions of flora and fauna are rigid geometric shapes. T-1223 and the V&A’s skirt cloth include rectangular borders on the horizontal and vertical edges of the garment where a geometric triangular pattern takes shape. These two garments share a similar deep maroon background in addition to motif and shape. This may indicate a similarity of dye colors originating from similar regions such as soga and morinda citrifolia.

Just as color and motif can help determine where the Cotsen fragment may have originated, a closer look at this textile’s pattern may give us a clue as to how the fragment originally functioned. Sarongs and kain panjangs, two types of Indonesian batik fashion, are often decorated with a triangular, geometric pattern that runs parallel to the garment’s vertical ends. This design is known as tumpal. We can see this pattern on the Cotsen fragment. The tumpal pattern of the Cotsen Collection’s garment is key to discovering the fragment’s original function. However, as tumpal is a common motif in sarong and kain panjang textiles, their differentiation requires a closer look.

The sarong is worn around a woman’s body with a length of nearly two yards. As present in a sarong from the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection (Fig. 10), two shorter edges are usually sewn together to form a circular, hip-hugging shape. [vi] The sarong has two main parts—the badan, the larger body of the garment, and the kepala, a perpendicular break in the middle of the garment. Because the two edges of the garment are sewn together, the kepala exhibits the sarong’s tumpal pattern. In the Met’s sarong, each side is sewn together with the tumpal’s triangular points facing one other. However, the Cotsen Collection’s garment T-1223 does not suggest a meeting of two triangle tips as would be present in the sarong style. Instead, the space above the triangles is open, exposing its geometric qualities. Therefore, T-1223 must not have been a part of a full sarong.

A kain panjang, as exemplified by the Victoria and Albert’s skirt cloth, maintains a larger, rectangular shape. No additional sewing brings parts of this textile together in tubular form, nor is a seam visible. Because of its wide size and shape, a kain panjang would reach the wearer’s ankles, and the tumpal would be on one or both sides (AS 26.27.2). The V&A’s skirt cloth, a kain panjang, has a similar layout to the Cotsen’s T-1223, as the tumpal patten of both garments signifies the end of the garment.

The tumpal pattern of the Cotsen Collection’s T-1223 garment is a central clue in placing the piece among a larger batik and potential placement on the body. As shown by the Met example, in sarong styles, two tumpal patterns appear connected by the bases or tips. As the Cotsen fragment’s tumpal pattern does not suggest a meeting of lines of triangles, there is no indication that edge pieces would be sewn together. T-1223’s tumpal has no mirror or visible seam, suggesting that the pattern is placed towards one singular edge, not cinched or sewn in the center. This characteristic aligns with the kain panjang style, where tumpal patterns often appear at the complete garment’s border or edge. In the Cotsen Collection’s garment, the tumpal stands alone; a rectangular border forms below the triangles’ base, and geometric patterns of various colors fill the background space. This harkens back to the V&A’s garment. Thus, the likelihood that this textile belonged to a once full kain panjang is compelling, as the kain panjang is neither connected to itself nor has two mirrored tumpal patterns.

The kain panjang typically serves a deep and meaningful purpose, which alludes to T-1223’s sacred history. While women mainly wear the sarong, the kain panjang is worn by either sex. The wear is different depending on the wearer; women wrap the garment right side over left, while men loosely fold the left side over the right. Because of this dual function, kain panjang is considered slightly more formal and higher-class than the sarong. Nonetheless, both are considered equally sacred. Therefore, the Cotsen garment is not only ornate in decoration but is rich in its societal and spiritual importance.

Because of its treasured past, Javanese batik is more than just a visual marvel. Significant importance lies within where it may fall on the body and who can wear such a garment. Therefore, contextualizing the Cotsen Collection’s fragment as a part of a whole textile adds to its validity, importance, and vibrant past. By looking at its details and past, categorizing the Cotsen fragment as kain panjang from the Cirebon region of Java brings it closer to its cherished history, as it, too, experienced life and spirituality alongside the individual who adorned its beauty.

Notes

[i] “Textile Terms,” The George Washington University Museum and The Textile Museum, accessed August 10, 2021, https://museum.gwu.edu/textile-terms.

[ii] Gittinger, Mattiebelle. Splendid Symbols: Textiles and Tradition in Indonesia. Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1985.

[iii] Muddin, Sattarat, Piyanan Petcharaburanin, Judi Achjadi, et. al. A Royal Treasure: The Javanese Batik Collection of King Chulalongkorn of Siam. River Books, January 2020.

[iv] Elliot, Inger McCabe. “Tales of a Trade Route Island.” In Batik: Fabled Cloth of Java. Singapore: Tuttle Publishing, 2013.

[v] Elliot, Inger McCabe. “Batik From the North Coast of Java.” In Orientations 15, no. 9 (September 1984): pp. 19- 21.

[vi] Ratuannisa, Tyar, Imam Santosa, Kahfiati Kahdar, and Achmad Syarief. “Shifting of Batik Clothing Style as Response to Fashion Trends in Indonesia.” In Mudra : jurnal seni budaya 35, no. 2 (2020): 127–132.