The Costen Textile Traces Study Collection houses nearly 4,000 textile fragments from various regions and time periods. While a significant portion of the collection is well-documented, some objects need more attention and research. The Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection T-0193.270 object was thought to be from Japan, however, there are some questionable elements in its origin.

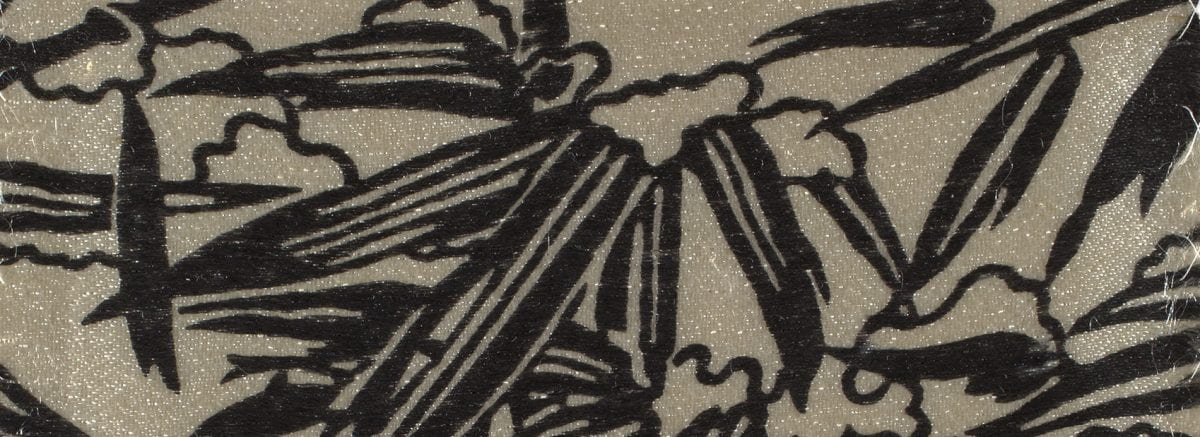

T-0193.270 was originally acquired by Lloyd Cotsen in 1998 from an art dealer in Munich, Germany, along with a large collection of samples from the Wiener Werkstätte, a cooperative of artisans in Vienna, Austria, active from 1903 to 1932. The textile’s general pattern, which features black bamboo pattern prints on cream satin weave silk, references the Japanese traditional stencil dyeing technique katagami. However, the abstract snow-like motifs and stylized bamboo leaves differ from the realistic snapshot of the bamboo silhouette often featured in Japanese stencils. Moreover, katagami’s final work, katazome typically involves dyeing the fabric surrounding the motifs, while the main motifs retain the fabrics’ original color from the dye resistant paste. This process results in lighter-colored motifs on a darker-colored ground. In contrast, the bamboo motif in T-0193.270 appears to be directly applied on the satin ground fabric. More likely, the object showcases the interplay of Japanese and Austrian artistic and design influences in the early 20th century.

From the late 19th century, the Western world was introduced to the rich and diverse visual arts, literature and cultural traditions of Japan, which had a significant impact on Western art and culture. Commodore Mathew Perry, strong armed Japan into signing the initial Treaty of Kanagawa on March 31, 1854. International expositions in London and Paris further promoted Japanese arts worldwide and helped inspire a movement known as Japonisme, a term originally defined by French critic Phillippe Burty in 1872 as “the study of the art and genius of Japan.”[i] Japanese garments, silks, and accessories became essential items for fashionable and “good taste” in the West in the 19th century.[ii] Bamboo, pine, flowers, insects and lotuses were popular motifs featured in clothing; they evoked the exotic elements of the East while also following the trend of nature in the West.[iii]

In the same era, due to Japan’s rapid shift towards industrialization and Western fashion, many Japanese traditional handcraft dyeing workshops went out of business and sold thousands of katagami stencils to collectors in Europe in the late 19th century.[iv] European collectors, museums and industrial organizations were able to purchase the stencils at a relatively low price. The Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie (current Museum of Applied Arts, Vienna) collected a massive amount of Japanese objects in 1907. The museum possessed more than 8,000 katagami stencils as part of donation from the German antiquary Heinrich Siebold (1852–1908) who served in the Austrian Embassy in Tokyo.[v]

The founders of Wiener Werkstätte, Josef Hoffman (1870–1956) and Koloman Moser (1868–1918) took inspiration from the plainness and simplicity of Japanese design. Moser studied katagami collections of Österreichischen Museums für Kunst und Industrie.[vi] His designs often included repetitive, flat, monochrome, asymmetrical and natural forms, which are core themes in Japanese arts and crafts. The other co-founder of Wiener Werkstätte, Hoffman, taught at the Vienna Kunstgewerbeschule (Vienna School of Arts and Crafts) between 1899 and 1936, and applied Japanese art principles in the classroom, encouraging students to use katagami stencils as a learning material.[vii]

Influenced by the founders, Wiener Werkstätte designers referenced other cultural sources to develop designs that represented the era and the mixture of cultures. Japanese naturalistic patterns inspired designers’ uses of line and planar space. While many Wiener Werkstätte designers’ works referenced Japanese patterns, they were not made with traditional Japanese techniques. The Wiener Werkstätte produced their simplified natural motifs and solid color patterns using the established European block print technique. Since the production department was composed of between 80 and 100 artists, it is difficult to ascribe a common trait to the 1,800 diverse designs.

While the exact origin of the Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection T-0193.270 object is still elusive, the influence of Japanese art, particularly katagami stencils, on Austrian design in the early 20th century, along with the divergence from traditional katagami design seen in the textile, suggests that the object was produced in Europe.

Notes

[i] Ono, Ayako. Japonisme in Britain: Whistler, Menpes, Henry, Hornel, and Nineteenth-Century Japan. London: Routledge Curzon, 2003.

[ii] Burnham, Helen, Jane E. Braun, and Sarah E. Thompson. Looking East: Western Artists and the Allure of Japan. First edition. Boston, Massachusetts: MFA Publications, 2014.

[iii] Burnham, Helen, Jane E. Braun, and Sarah E. Thompson. Looking East: Western Artists and the Allure of Japan. First edition. Boston, Massachusetts: MFA Publications, 2014.

[iv] Humphrey, Alice. Katagami: The Craft of the Japanese Stencil. London: Museum of Domestic Design and Architecture, 2017.

[v] “Collection Asia,” MAK Museum Wien. Accessed May 14, 2021, https://mak.at/sammlung/mak-sammlung/sammlung_asien.

[vi] Völker, Angela, and Ruperta Pichler. Textiles of the Wiener Werkstätte 1910-1932. London: Thames and Hudson, 1994.

[vii] Susuda, Miwa. Japanese Influence on Wiener Werkstätte Design: A Case Study of a 1920’s Dress. New York: Fashion Institute of Technology. 1999.