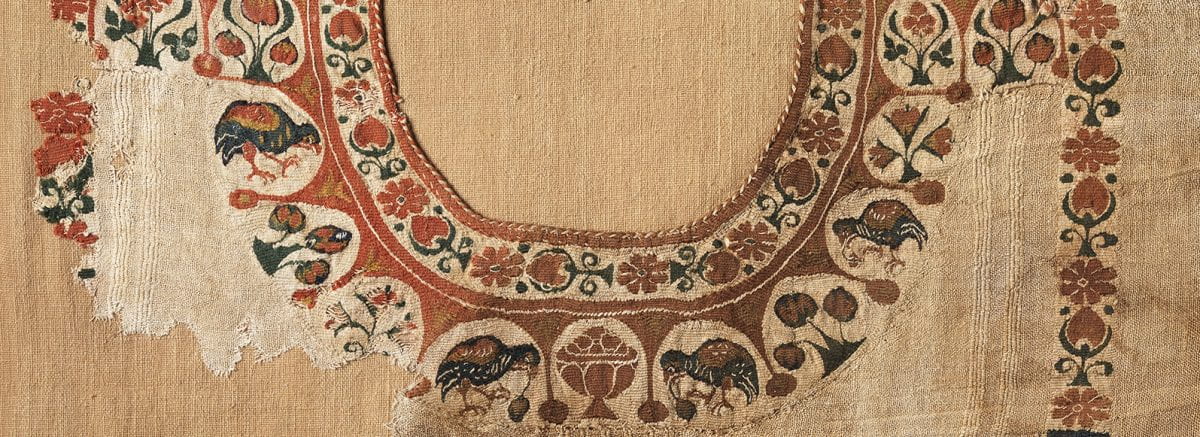

On April 26, 2001, Lloyd Cotsen acquired a tunic fragment from the art market in Los Angeles. The textile fragment (T-1110) originates from Egypt and dates sometime between the second and fifth centuries CE. Even though it is small in size, the various details emerging on the surface of this fragment, allow scrutiny of the delicate craftsmanship. Belonging to a Late Antique tunic, the woven ornamentations of the fragment once decorated the shoulders, neckline, and sternum of its owner. The craftsman used the renowned tapestry technique and employed undyed linen for the tunic’s background and wool for its polychrome ornamentations. Motifs of red, green, purple, black, and yellow populate the surface of the fragment. The exterior border, composed of alternating rosettes and flower buds, delineates the tunic’s collar. A fragmentary green detail to the right suggests that this visual repertoire extended to the shoulders. A vertical band with floral ornamentations and a fish hangs to the right. Arched niches with globular terminals, from which emerge foliage and birds, appear in the inner border. At the center of this border emerges a basket. The vibrancy of the textile commands the viewer’s attention!

The Late Antique period witnessed a shift in the understanding of media. This textile fragment, and others, allow us to consider how the Late Antique people understood the objects and architecture around them. By navigating through the secular to the sacred spheres of Late Antique society, I study the socio-economic perceptions of the beholder when viewing these textiles. I question how these perceptions carry or shift in the early Christian visual narrative, both through the study of textiles and architectural decoration. Examples of literary ekphrases examined in this essay are testaments to this new understanding of imagery and materials. The fourth-century bishop, Asterius of Amasia, in his first Homily, wrote:

They have invented some kind of vain and curious broidery which, by means of the interweaving of warp and woof, imitates the quality of painting and represents upon garments the forms of all kinds of living beings, and so they devise for themselves, their wives and children gay-colored dresses decorated with thousands of figures. . . . When they come out in public dressed in this fashion, they appear like painted walls to those they meet.[i]

Asterius explained that multicolored woven yarn or embroidered threads allowed for skillful weavers to imitate the qualities of other mediums, in this instance, that of painting.

Neck ornament, Egypt, c. 3rd–4th century CE. Wool, linen, and gold-wrapped silk thread, slit tapestry; 57 x 16 cm. Courtesy of Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 46.401.

Late Antique artists used wool to imitate silk. Wool, a lower-cost material, was preferred by weavers because they could dye it easier and bring forth the qualities of silk.[ii] Individuals unable to ornament their garments with expensive gemstones and silk applied wool bands, known as clavi, or patches known as segmenta or medallions to their tunics. These woolen embroideries emulated the qualities of silk, gold, and sometimes gemstones. Nevertheless, the need to acquire or imitate the most expensive materials seems to have been highly criticized. In a passage, Asterius explained that:

If you abandon the sheep and the wool, and the indispensable provisions of the Creator of all, leading yourself astray by vain notions and capricious desires, and seek after silk, and join together the threads of the Persian worms, you will weave the windy web of a spider. And then, you come to the dyer of bright colors, and pay hefty sums to have the shell-fish drawn out from the sea, and anoint the garment with the blood of the animal. This is the deed of a wanton man, who abuses his property for want of a place to expend its superfluity. And for this reason such a one is attacked, accused by the gospel as an effeminate idiot, adorning himself with the adornments of wretched little girls.

Yet, one thing is for sure, the majority of Late Antique buyers desired to demonstrate their luxurious and cosmopolitan taste, and they would have never preferred to wear an undecorated tunic. However, from Asterius’s commentary, it becomes clear that such aesthetic choices were criticized by some. Hence, Asterius argued that shifting away from materiality led pious men and women closer to God. To his disappointment, however, people even purchased woven images of Christ and other saintly figures. As he explained:

The more religious among rich men and women, having picked out the story of the Gospels, have handed it over to the weavers –I mean our Christ together with all His disciples, and each one of the miracles the way it is related. . . . In doing this they consider themselves to be religious and to be wearing clothes that are agreeable to God. If they accepted my advice, they would sell those clothes and honor instead the living images of God. Do not depict Christ (for that one act of humility, the incarnation, which he willingly accepted for our sake is sufficient unto Him), but bear in your spirit and carry about with you the incorporeal Logos. Do not display the paralytic on your garments, but seek out him who lies ill in bed.

Even with the empire’s conversion to Christianity over the course of the fourth century, the cultural traditions of the late Romans endured. For instance, woven gemstone imitations border the Old Testament scene on a late fourth-century textile (see below). Of interest is that Asterius’s ekphrasis about textiles differs from the ekphrases of writers of the fourth to the sixth centuries engaging with sacred textiles and architecture. It appears that throughout this period, viewers start to develop highly sensitized experiences due to the vivid effects of these sacred objects and spaces. One may argue against Asterius and explore how these visual effects aimed to bring the beholder closer to the Christian tradition.

Paulus Silentiarius, in a poem he recited in 563, described the visual effects appearing on the surface of textiles from Hagia Sophia. In the following excerpt, the poet and courtier communicated his wonderment caused by the illuminations of the gold-wrapped silk thread on the church’s altar cloth. Describing the effects of the gold, he wrote:

Let my bold voice be restrained with silent lip lest I lay bare what the eyes are not permitted to see. . . . Unfold the cover along its four sides and show to the countless crowd the gold and the bright designs of skillful handiwork. . . . This has been fashioned not by artist’s skillful hands plying the knife. . . . Upon the divine legs is a garment reflecting a golden glow under the rays of rosy-fingered Dawn. . . . The whole robe shines with gold.

Paulus Silentiarius’s ekphrasis opposes that of Asterius. Decorating the holy table on which the bread and wine are consecrated in communion services with a silk and gold textile only further bolsters the medium’s connection to the sacred. Further on, Paulus Silentiarius wrote that “while rising above their immortal heads a golden temple enfolds them with three noble arches fixed on four columns of gold.” This sentence from the excerpt points us to the use of gold in architectural decoration.

Starting from the early fourth century and continuing until the sixth century, texts describe the illuminative atmosphere in these interior spaces caused by gold. For instance, Gregory Nazianzenus, on his eighteenth Oration, in which he described the dome of the Martyrium at Nyssa, wrote, “At the top is a gleaming heaven that illuminates the eye, all round with abundant founts of light – truly a place wherein light dwells.” Inside the Martyrium at Nyssa, gold emulated heaven and provided the beholder with the visually golden spirituality expected to linger on the interior surfaces of such a holy space. One may assume that once the pilgrim stepped into the church, the strategically employed decoration activated the senses to better facilitate this divine experience.

Procopius, writing on Hagia Sophia, explained that the entire ceiling of the church was overlaid with pure gold, combining beauty with ostentation.

One must say that its interior is not illuminated from without by the sun, but that the radiance comes into being within it, such an abundance of light bathes the shrine. So the vision constantly shifts, for the beholder is utterly unable to select which particular detail, he should admire more than all the others.[iii]

Paul Silentiarius, in his description of Hagia Sophia, also referred to the impeccable qualities of light. He wrote:

Thus, is everything clothed in beauty; everything fills the eye with wonder. But no words are sufficient to describe the illumination in the evening: you might say that some nocturnal sun filled the majestic temple with light.

The interior decoration, as presented in the mosaics of Hagia Sophia, emulates patterns that were derived from textiles. The ornamentation prompts us to identify the space as a woven interior. The interplay between gold and light disorientated the viewer. The moment one stepped into a church, the beholder was transported into an otherworldly world, blurring the lines between the terrestrial and celestial spheres. The same thing occurred via textiles; they also aimed to disorient the viewer through the emulation of other mediums (see gemstones on fragment below). This is precisely why Asterius criticized them. For Asterius, they disorientated the owner and beholder from maintaining and representing the values of the Late Antique Christian society.

Art historian Jas Elsner defines ekphrasis as having the ability “to bring what is described before the reader’s or the listener’s eyes. The role of ekphrasis is to make the reader or the listener ‘see’ more than they saw before, when they encounter the object next.”[iv] As has been demonstrated, Late Antique authors, triggered by the optical effects of materials, strove to write about them and their qualities. The reciprocation between language and the visual developed an ekphrasis that constantly attested to these visual signifiers and metamorphoses. To that end, I would like to propose reconsidering textiles, not as mere ornamentations of space and body. What can we learn from ekphrasis of architectural surfaces, and how can we parallel these visual effects and sensations to textiles?

Notes

[i] Mango, Cyril. The Art of the Byzantine Empire 312-1453: Sources and Documents. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1986.

[ii] Thomas, K. Thelma. Designing Identity: The Power of Design in Late Antiquity. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2016.

[iii] Roberts, Michael. The Jeweled Style: Poetry and Poetics in Late Antiquity. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2010.

[iv] Elsner, Jaś. “Art History as Ekphrasis.” Art History 33, no. 1 (2010): 10–27.

Further Reading

Abdel-Malek, Laila Halim. “Deities, Saints and Allegories: Late Antique & Coptic Textiles.”

Hali Magazine 71 (1993): 80-89.

Diebold, William. “Medium as Message in Carolingian Writing about Art.” Word and Image 22

(2006): 196-201.

Mitchell, Victoria. “Drawing Threads from Sight to Site.” Textile, 4:3 (2006): 340-361.

Stauffer, Annemarie. Textiles of Late Antiquity. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013.

______. “The Medium Matters: Reading the Remains of a Late Antique Textile.” In Reading

Medieval Images: The Art Historian and the Object, edited by Elizabeth Sears and

Thelma K. Thomas, 39-49. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2002.

Weitzmann, Kurt. Age of Spirituality: Late Antique and Early Christian Art, Third to Seventh

Century. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1979.