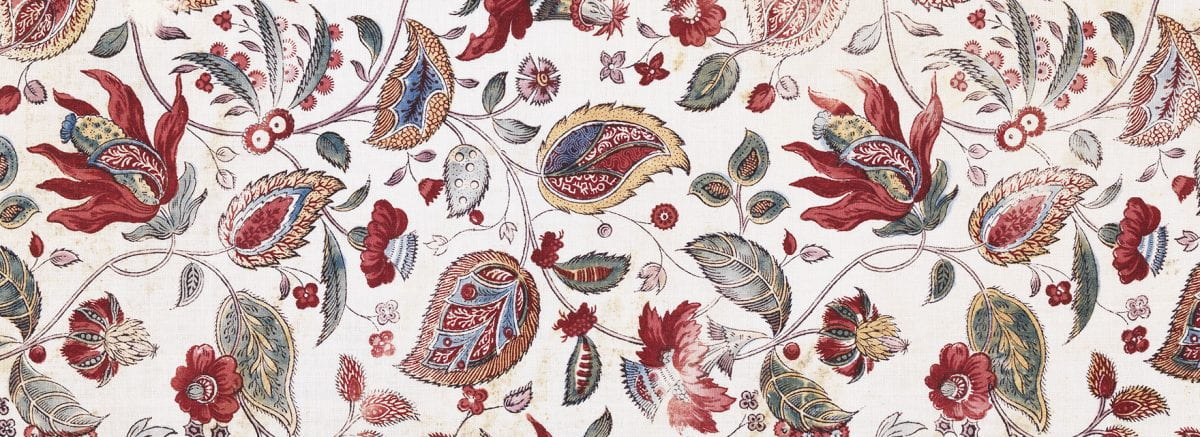

This fragment from the Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection (T-0453) is known as an “indienne” in French and as “chintz” in English. Though produced in France, it is part of a period, 1600-1800, in which Europe imported printed cottons by the millions from India. These imported cottons were brightly colored, with elaborate floral motifs. Shortly after the textiles entered the European market, Europeans began to produce their own. While it is part of an important European textile tradition, the specific details about this example remain sparse. The design of the fabric is not unique to the Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection. It also appears in the collection of the Victoria and Albert Museum and in a catalog for the exhibition Indiennes Sublimes: Indes, Orient, Occident, costumes et textiles imprimés des XVIIIe et XIXe siècles [i]

The details about the fabric from the Cotsen collection, the V&A and the Indiennes Sublimes exhibition catalog both complement and contradict one other. All three identify the object as a block-printed cotton made in France in the late 18th century. The V&A and Indiennes Sublimes catalog narrow the region to the Haut Rhin, a northeastern part of France that borders Switzerland and Germany. Yet they locate the place of production in different cities of the region, in Münster and Mulhouse, respectively, with the exhibition catalog narrowing the fabric to a specific maker and potential factory – Hartmann et Fils. The dates from each source present similarly conflicting information – circa 1780 for the Cotsen fragment, 1795-1810 for the V&A example and late 18th century for the Indiennes Sublimes example. Examining the economic and cultural context in which these fabrics emerged explains why their biographical details both converge and diverge.

Printed cottons first emerged in India, where cotton could be easily grown, and Indian craftspersons had developed mordant and resist-dyeing techniques that allowed dyes to be colorfast. There is evidence that India exported its printed cottons as far back as 3000 BCE.[ii] By the medieval period, these printed cottons were a primary driver of the international economy.[iii] When Europeans arrived at the Indian subcontinent in the 16th century in search of Indonesian spices, they found a vibrant Indian Ocean trading network built upon the exchange of printed cottons. While Europeans had initially sought to trade European linen and wool, they soon discovered these textiles held little value for Indonesians, who instead desired India’s printed cottons. India, too, rejected European textiles, eager rather for precious metals such as silver, gold and copper. Europeans thus first engaged with printed textiles as Indian Ocean merchants – exchanging metals for the colorful cotton from India, which they then took to Indonesia to trade for spices to bring back to Europe. By the early 17th century, European nations who had been trading in the region during the 16th century established a variety of official, national Indian trading companies, including the British East India Company in 1600, Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie (Dutch East India Company) in 1602 and a Danish trading company in 1616. The French did not establish their trading company, the Compagnie Royale des Indes Orienteles, until 1684.[iv]

Printed cottons eventually found their way to European markets as well, arriving most significantly in the form of palampores – large, colorful cottons with a central, tree-of-life motif from whose branches stylized flowers, leaves and birds flowed. Palampores were used primarily as furnishing textiles, particularly in bedrooms. Europeans also adopted chintz as dress fabric (Fig. 5). Unlike non-colorfast linen or delicate silk, the cotton fabric could be laundered and cleaned regularly without losing its color or degrading, making it a much more hygienic and comfortable colorfast clothing option – particularly for the summer months. A craze for the Indian printed cottons swept Europe. By 1625, Europeans were sending patterns to India to produce designs for the European market. By the 1680s, “57 percent of French cargoes were constituted specifically of painted Indian chintz.”[ii] Initially confined to the elite classes and seen as a luxury fabric, printed cottons became increasingly more available to the bourgeoisie and middling classes.

As the trade in chintz reached its apogee, in an effort to protect national industries such as the silk weaving of Lyon or wool production in England, nations across Europe enacted bans and duties on the importation of foreign fabrics and the local production of imitations. France enacted one of the first of these laws in 1686, banning completely the importation of printed cottons or the production of their imitations, closing printing shops and going as far as to destroy manufacturing sites. While these laws pleased the merchants and laborers associated with the industries threatened by imported fabrics, they did not please consumers who, over the course of the 17th century, had developed a strong taste for the brightly colored cottons. The laws also angered merchants and local producers who stood to benefit from the trade of foreign textiles and the production of their imitations. As such, consumers, merchants and producers found ways to circumvent these laws, some by outright smuggling. Because the laws did not apply to exports and often applied only to cotton fabric and not to the cotton-linen blend known as “fustian,” others found ways to continue locally producing imitations. Thus, despite the bans, a nascent cotton printing industry developed in France from the late 17th to mid-18th century. It developed even further in locations with slightly less restrictive bans, including Switzerland, Germany and independent cities in France – including Mulhouse – not subject to the bans.

France participated heavily in the transatlantic cotton and textile trade. It lifted its printed cotton importation and production ban in 1759. In response, a slew of factories opened, “heralding the beginning of a golden age of prosperity for the French printed cotton industry” while also insinuating the country further in transatlantic trade.[v] The Oberkampf factory in Jouy-en-Josas, outside Paris, was the most famous of the printed textiles manufacturers. There were, however, hundreds of printed cotton factories across France, from Mulhouse to Rouen to Marseille to Nantes. Mulhouse, in particular, was a main center for the production of printed cottons, having not been subject to the French importation and imitation bans. The first factory of the Mulhouse region, Schmaltser et Cie, was erected in 1746. By 1786, the city had 19 workshops and printed 146,544 pieces of cloth annually. The French industry shifted constantly. Firms were bought and sold frequently. They often merged or formed partnerships. Some firms dissolved and then re-emerged with the same managers but under a completely new name. The turbulence in the industry renders it difficult to make design and production attributions. Additionally, firms borrowed or copied designs from other firms, further complicating the attribution process. The result is a profusion of brightly colored, floral fabrics – all with similar motifs and many with the same designs.

Samples of these fabrics can be found in museum collections across Europe and North America, and it is possible to find the same design in multiple institutions. Yet the biographical information for these pieces often differs. Far from casting doubt on our understanding of cotton woodblock-printed textiles, the divergent details instead exemplify the complex, interwoven history of these fabrics. From their origins in India to their entry into Europe to their domestication in France and subsequent trade across the continent and world, “les indiennes” were important economic and cultural commodities. The fragment from the Cotsen Textile Traces Study Collection is a part of this elaborate, international history. It is a single fragment that helps tell the global story of printed cotton textiles.

Notes

[i] Villa Rosemaine. Indiennes Sublimes: Indes, Orient, Occident, costumes et textiles imprimés des XVIIIe et XIXe siècles. Toulon, France: Galerie de la Villa Rosemaine, 2011. https://villa- rosemaine.com/en/node/36.

[ii] Fee, Sarah. “Indian Chintz: Cotton, Colour, Desire.” In Cloth That Changed the World: The Art and Fashion of Indian Chintz., edited by Sarah Fee. Toronto: Royal Ontario Museum, distributed by Yale University Press, 2020.

[iii] Guy, John. “‘One Things Leads to Another’: Indian Textiles and the Early Globalization of Style.” In Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800, edited by Amelia Peck. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013.

[iv] Watt, Melinda. “‘Whims and Fancies’: Europeans Respond to Textiles from the East.” In Interwoven Globe: The Worldwide Textile Trade, 1500-1800, edited by Amelia Peck. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2013.

[v] Grant, Sarah. Toiles de Jouy: French Printed Cottons. London: V&A Publishing, 2010.